This past week, the History department chair sent out an e-mail with the subject line “Grim News.” In the e-mail, she detailed extensive cuts to the History department’s funding, apparently emerging from the Provost’s office. Among the cuts are:

- The Public History faculty line I recently vacated

- 2/3 of the funds we use to support graduate assistants

- Two lecturerships

- A visiting lecturership

- All adjunct funding

I’ll have something more substantive to say about this soon, but right now I’m grief-stricken.

In the meantime, you can read this Idaho Statesman article to get a sense of the university’s party line. As you might imagine, though, “declining enrollment” is not the whole story.

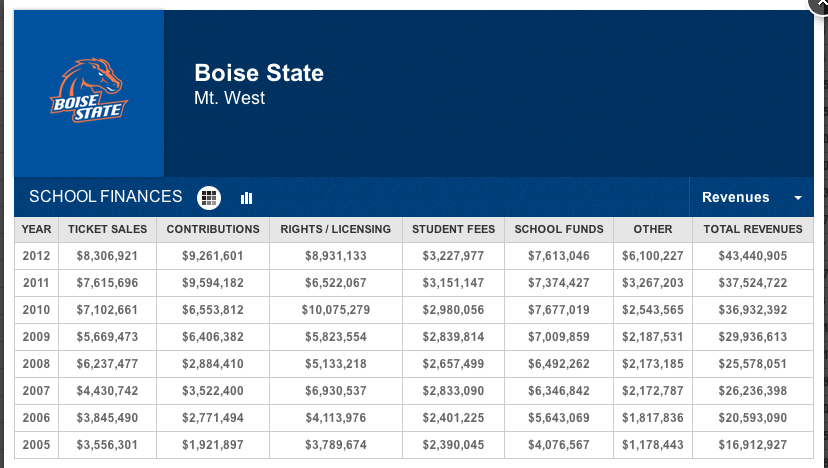

I’ll leave you with these tidbits, calculated by one of our endangered lecturers, who used to work in college finance and administration:

The department offered 49 full-semester 3-credit courses with 1,385 students total in Spring 2015. Of these:

- 17 classes with 556 students were taught by tenure/tenure-track faculty (41%)

- 15 classes with 449 students were taught by 3.5 lecturers (33%)

- 14 classes with 340 students were taught by 8 adjuncts (24%)

- 3 classes with 40 students were taught by full-time faculty not housed entirely in the history department (2%)

The lecturer estimates the department’s instructional expenses constitute less than 45% of the revenue it brings in through teaching alone, and that there’s no way the now diminished tenure-line faculty can accommodate all of the students currently being taught by lecturers and adjuncts. Even trying to accommodate them will mean History faculty won’t have time to do research during the academic year. Currently we have two NEH fellows, an NSF fellow, a Fulbright scholar, and the editor of a top journal—as well as everyone else’s research agendas—so our department isn’t exactly shirking its research responsibilities. Many of us have also service commitments that already are untenable.